A well in Algeria. A new report says the country will find it hard to offset falling production. (Anadarko)

A well in Algeria. A new report says the country will find it hard to offset falling production. (Anadarko)

New projects will not be able to compensate for the drop in Algerian gas reserves, according to a UK thinktank.

The development of "small and costly reservoirs" is not enough to stem the decline of the huge Hassi R’Mel field, warned a report published on Monday by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), called Algerian Gas: Troubling Trends, Troubled Policies.

According to Ali Aissaoui, the report’s author, subsurface issues and above-ground problems at the 60-year-old gas field will be difficult to overcome with current enhanced recovery techniques but need to be tackled swiftly to prevent a significant drop in Algerian production.

"Not only will the new upstream projects hardly make a difference in compensating for the decline of Hassi R’Mel and other mature fields, but most of them are tight, dry, or, in the case of southwestern formations, have high [carbon dioxide] content [and are] therefore too costly to be able to offset the notable shortfall in government revenues," the report said.

Aissaoui notes that Algeria’s state-owned Sonatrach is "increasingly being perceived as structurally short on gas supply". Proven reserve estimates were downgraded by the Algerian government in November 2015 to 2.75 trillion cubic metres compared with previous estimates of 4.5 tcm.

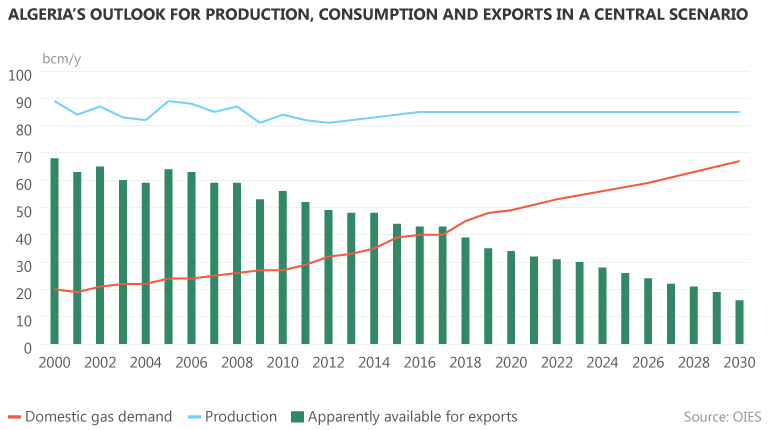

According to the report, Sonatrach could be exporting just 15 billion cubic metres per year by 2030 compared with the current figure of 45 bcm/y. The utilisation rate of the country’s export capacity has already fallen to 52%. To stem the decline in production at maturing fields, new gas compressor lines and measures to upgrade and debottleneck facilities are being planned, but they have not yet been put in place.

Consultancy Amec Foster Wheeler was brought on board at Hassi R’Mel last year to diagnose, design and optimise surface flows at the field. But this will address only part of the problem, as the sub-surface water penetration issue seems to be especially difficult to tackle. Enhanced recovery is made more complicated by the fact Hassi R’Mel acts as the central processing facility for Algerian gas production.

"Some informed sources believe that if Sonatrach fails to make rapid progress in this area, other options may have to be considered including offering takes in the [Hassi R’Mel] field to major companies that could integrate the latest sub-surface technologies and help solve the field’s large-scale surface optimisation problems," the report said.

The move would be politically sensitive as both Hassi R’Mel and the super oil field Hassi Messaoud have "acquired huge symbolic significance". Aissaoui told Interfax Natural Gas Daily on Friday that the idea of opening up the field to foreign investors is not new – the move was contemplated in the 1990s by the government of former Prime Minister Sid Ahmed Ghozali. However, this triggered "an emotional response that blocked out reason and logic", Aissaoui said. "We should expect the same if this is what the current government really has in mind and on the agenda," he added.

Aissaoui stated in the report that the government should confirm and disclose any details regarding bilateral deals being struck with IOCs "otherwise [the rumours] will only add to investment uncertainties prevailing in the country".

Too little, too late?

The government’s current plans to prevent the decline in production could be too little, too late, according to the report. On the demand side, the country is tackling the subsidy-fuelled increase in domestic consumption by reducing the need for gas in power generation, which represented almost 48% of Algeria’s domestic demand in 2015.

However, at a conference of the Association Algerienne des Industries du Gaz in February, Noureddine Boutarfa – president of state-owned utility Sonelgaz – highlighted the technical issues surrounding the government’s plan to introduce 22 GW of renewable capacity to the energy mix by 2030. He pointed out the current roadmap will need some fine tuning, especially with regards to storage, and that gas would be necessary as a bridging fuel.

And while Algeria has been able to increase its domestic gas prices in an attempt to curb demand – a politically acceptable move in the context of low oil prices, according to the OIES report – they still remain the cheapest in the Middle East and North Africa.

A problem facing the government is that any policy change will be inexorably slow because of the "precarious social and political balance" as "snowballing demand" remains a tangible risk, the report said. Another part of the government’s plan, according to Aissaoui’s analysis, is to develop conventional gas fields near existing ones, but this is unlikely to yield much more output.

Meanwhile, shale still holds great potential. Unconventional resources are a low priority for the government because of public protests and the high cost of extraction, but estimates show reserves could amount to 20.3 tcm – more than seven times the country’s revised proven conventional reserves.

There are also good prospects for increasing conventional reserve estimates in the Trias/Ghadames, Illizi and Grand Erg/Ahnet regions by roughly 1 tcm, according to United States Geological Survey data from 2012.

This article was amended on Monday 23 May at 3.07pm to correct the figure given for Algeria's current gas exports.

Talk to us

Natural Gas Daily welcomes your comments. Email us at [email protected].