Saudi market share drive intact despite change at top

Khalid al-Falih, Saudi Arabia’s new oil minister. (World Energy Congress)

Khalid al-Falih, Saudi Arabia’s new oil minister. (World Energy Congress)

When veteran Saudi Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi was replaced earlier this month in the job he had held for 21 years by Khaled al-Falih, the former head of state oil firm Saudi Aramco, the kingdom’s PR machine was at pains to emphasise it would be business as usual at the world’s largest oil exporter. Despite that, conflicting theories have emerged about Saudi Arabia’s future energy policy.

Naimi was often credited with being the architect of the kingdom’s decision in late 2014 to abandon its swing producer role within OPEC. Various conspiracy theories, more or less off-beat, surrounded that decision, although Saudi oil officials have repeatedly said it was taken to better serve customers by pumping oil at the volumes they required – not to boost market share, not to kill off light tight oil in the United States, and not to cause a slump in oil prices as part of a conspiracy to undermine the economies of Russia and/or Iran.

When the famous Saudi Oil Minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani was ousted from his post 30 years ago after a disastrous plunge in oil prices to below $10 per barrel – also the result of an OPEC market share war – his successor Hisham Nazer quickly reversed the policy and oil prices soared. But conjectures that the new Saudi minister would be more amenable to a production freeze have so far proved wide of the mark.

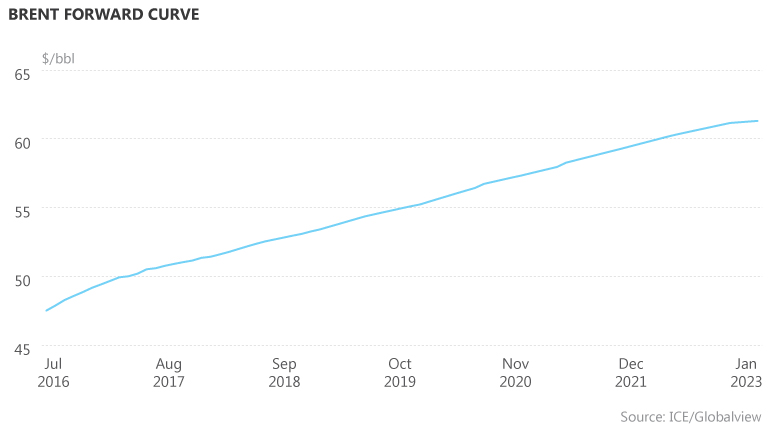

Within days of Falih stepping into Naimi’s shoes, the head of the kingdom’s state-owned oil company appeared to suggest Saudi Arabia may pump more oil rather than less if demand improves and the market rebalances. Aramco Chief Executive Amin Nasser said his company would meet customer demand, and he predicted supply and demand would move into balance by the year-end. "If it means we need to increase our output, we will do it," he said.

This could be read as a restatement of the business-as-usual policy. Importantly, however, Nasser’s comments reiterated that Saudi Arabia is not yet ready to freeze production. The remarks appear to make the prospect of an OPEC deal to set a ceiling on production more remote – but as there is always horse-trading around the outcome of such meetings, a deal cannot be ruled out.

Wrecked agreement

The 13 members of OPEC are due to meet in Vienna on 2 June. OPEC and non-OPEC members were in Doha in April for a meeting that had been expected to seal a tentative agreement to freeze production made between Russia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela in February. Instead, the market witnessed a rare fiasco – the carefully orchestrated deal unravelled at the last minute after Saudi Arabia decided not to sign unless Iran joined the production freeze, which it had already ruled out.

Some commentators believe the Doha deal was scuppered by the Saudi ruling elite because of their country’s geopolitical rivalry with Iran. The Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman said before the Doha meeting that no deal would be signed unless Iran was a part of it. He also said the kingdom could boost production to 11.5 million barrels per day immediately if necessary, although the reality is that this would take longer to deliver on a sustained basis.

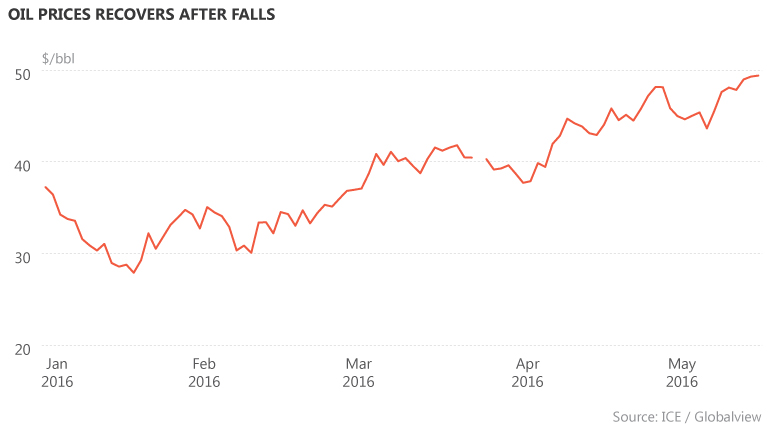

As with Nasser’s remarks, this could be read in two ways: as a veiled threat or as a restatement of Saudi Arabia’s goal to meet its customers’ needs, whatever the level required. But the latter interpretation is almost certainly correct. Saudi Arabia has suffered from the oil price fall, as have other producers, and it has no incentive to drive down prices that are just beginning to recover. If the country sticks to its policy, it stands to benefit when the market rebalances. Supply disruptions, falling US oil production and a weaker dollar have helped boost prices to $48/bbl in May, up by two-thirds from this year’s lows of around $27/bbl.

Naimi had been in the post since 1995, and his departure had long been expected as he is now 80 years old. The choice of the highly experienced Falih as his successor appears to reflect the need for policy continuity. The real significance of the change at the top may be institutional rather than marking changes in how much will be pumped.

The ministry over which Falih will preside has been renamed the Ministry of Energy, Industry and Mineral Resources, suggesting he will prioritise diversifying the economic resources available as part of the Vision 2030 initiative rather than micro-managing the oil price.