EU countries fall behind 2020 renewables targets

The UK's Llyn and Inner Dowsing wind farm. Along with France and the Netherlands, the UK is likely to fall short of its 2020 renewable targets. (Centrica)

The UK's Llyn and Inner Dowsing wind farm. Along with France and the Netherlands, the UK is likely to fall short of its 2020 renewable targets. (Centrica)

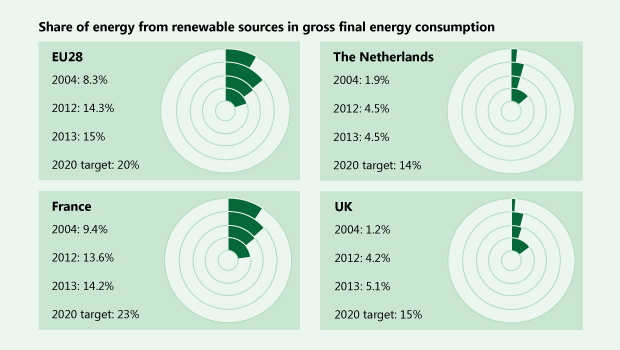

The UK, France and the Netherlands are still far from meeting their legally binding 2020 renewables obligations, data released by Eurostat confirmed this week.

The data showed that the share of renewable sources in the EU’s gross final energy consumption reached 15% in 2013, up from 8.3% in 2004 – the first year for which data is available. The aggregate target for the 28 member states combined is for renewables to make up 20% of gross final consumption by 2020.

The 2020 target is based on effort sharing between member states, however, and national targets vary significantly – from 49% in Sweden to 10% in Malta.

The data confirmed that three member states in particular will find it challenging to meet their 2020 obligations for renewables. The UK is 9.9 percentage points behind its national target of 15%, the Netherlands is 9.5 percentage points behind its goal of 14% and France is 8.8 percentage points short of its 23% target.

With little more than five years to fill the gap, it remains highly uncertain whether national subsidy schemes in these countries will attract enough new investment in renewables. There are also concerns over security of supply in the longer term, as a number of gas- and coal-fired plants in the UK and Netherlands are being closed as a result of unprofitability or regulatory intervention.

“A total of 4.45 GW of offshore wind and 6 GW of onshore wind will have to be built in the Netherlands to reach the 2020 target. It is a race against time and it is hard to say if the target will be met,” Saskia Lavrijssen, professor of energy law at the University of Amsterdam, told Interfax.

In the Netherlands, the government is using tax revenues to subsidise new investment in renewables – a policy permitted under the EU’s Energy and Environmental State Aid Guidelines.

“The Dutch government is providing subsidies to fill the gap between grey and green energy. The total amount available for developers of renewables in 2015 is €3.5 billion [$3.7 billion],” said Lavrijssen.

Investor confidence

Marinus Winters, an Amsterdam-based energy lawyer with Allen & Overy, said government subsidies earmarked for offshore wind power projects could create renewed investor confidence in the sector.

“The Netherlands has changed its subsidy regime for renewables three times over the last 10 years. I think that partly explains why the increase in renewables deployment has been slow,” Winters told Interfax.

“But investor confidence is increasing. We see a lot of projects in the pipeline, particularly for offshore wind power. The Dutch government has earmarked €18 billion for subsidies for offshore wind until 2023, with the first tender for projects taking place by the end of this year,“ he added.

In the UK, contracts for difference (CfDs) – a guaranteed minimum price (‘strike price’) for electricity produced – apply to new renewables and nuclear installations. CfDs replace the Renewables Obligation (RO) system, which expires in 2017. Whether the new scheme is generous enough to foster development in new, capital-intensive offshore wind projects remains in question, however.

“There are mixed signals for investors. Wholesale electricity prices are low, and in absolute terms the CfD system offers lower returns for a shorter period of time compared with the RO system, and may therefore appeal more to established investors. On the other hand, CfDs guarantee cash flows and this could appeal to investors that are seeking low risk, guaranteed returns in a low-interest environment,” Amee Shokur, director of corporate ratings at Fitch, told Interfax.

Increasing the share of renewables by almost 10% over the next five years to reach the 2020 target nevertheless seems a daunting task for the UK.

“The UK will find it hard to meet its 2020 renewables target for two reasons in particular. Firstly, energy bills are high and there is a lot of focus on this ahead of the general election in May. Renewables technologies are expensive – particularly for offshore – and costs will have to be passed on to end-users,” said Shokur.

“Secondly, the supply-demand margin in the UK is narrow and intermittent supply from renewables will not help expand this gap,” she added.

In France there is also widespread scepticism about whether the 2020 renewables target will be met. The French government has outlined plans for an energy transition to reduce the share of nuclear power and increase the use of renewables, but the French Senate remains divided on the way forward.

“Replacing nuclear power with renewable sources would necessitate significant investments in the network – estimated at €210 billion – and would not reduce much CO2 emissions,” Pascale Scapecchi, a professor in economics at Aix-Marseille University, told Interfax.