Bear market hall of fame

Natural Gas Daily examines reactions to the new bear market reality in eight countries and reviews what NOCs and IOCs are doing to limit their losses.

The collapse in oil prices has taken its toll on the global energy industry and on economies linked to selling or buying oil and gas. In the first in a series of extended features focusing on key industry trends, Natural Gas Daily examines reactions to the new bear market reality in eight countries and reviews what NOCs and IOCs are doing to limit their losses.

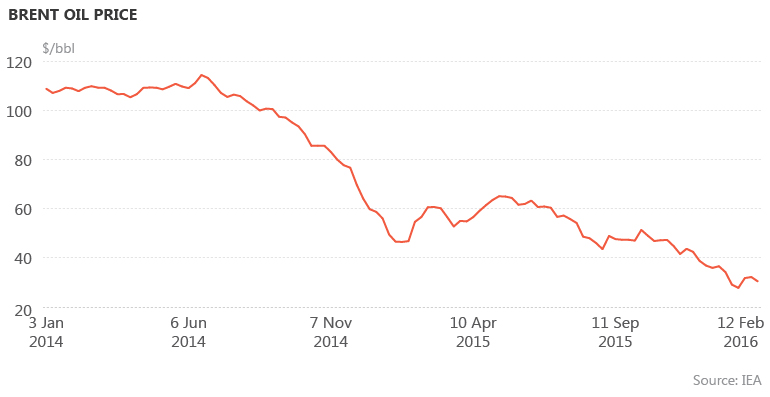

Oil prices began to tumble in the first half of 2014, but with many gas and LNG sellers having linked their contracts to oil with a typical six-month time lag, the full effect of the crash was not felt until late 2014 or early 2015. In terms of sales strategy, the shift from a sellers’ market to a buyers’ market resulted in a change in global dynamics, leaving buyers and sellers seeking new terms to adjust to the altered environment.

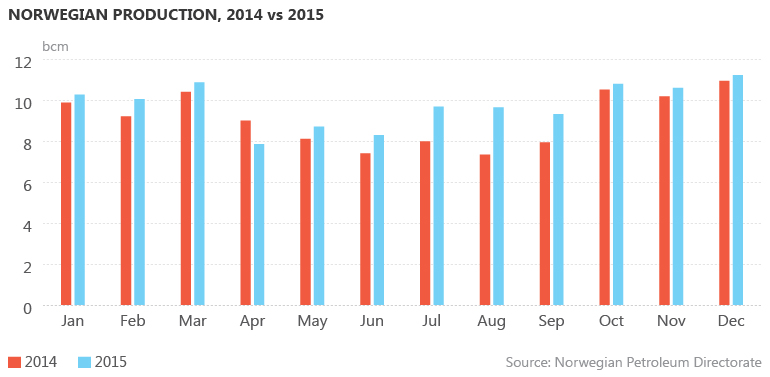

Norway’s new flexible pricing structure, which features contracts linked to regional hub prices, saw the country deliver record high volumes of gas into Europe in 2015, while Gazprom’s historical reluctance to consider a shift towards hub indexation in its contracts saw buyers turn to alternative sources of supply.

Although many industry players have changed their contract terms and adjusted their prices, companies in the gas industry are continuing to look at cost-saving measures – laying off staff, slashing capital expenditure and selling assets – or, in some cases, declaring bankruptcy. The situation is unlikely to improve in the near term.

While Saudi Arabia and Russia have agreed to cap oil production, there is no indication a material cut in output will be forthcoming, so a significant price rally is not on the cards. Prices of $30/bbl are clearly unsustainable in the long term, but even when prices do tick up, few expect to see oil above $100/bbl by the end of the decade, or maybe ever again. For now, the bears are in charge – and the pain looks set to continue.

Norway

Norway extended its flexible pricing structure and delivered record volumes of gas to the rest of Europe in 2015. The country sent 108 billion cubic metres to Germany, Belgium, France and the UK – an increase of 7 bcm from 2014 – with export values reaching well over NOK 400 billion ($46.6 billion).

But the Norwegian economy is starting to feel the impact of persistently lower oil prices. Norway’s tax revenue in 2015 fell by around 40% year on year, to NOK 104 billion, according to the country’s tax statistics for 2015.

The lower income has also started to feed into the mainland non-oil economy, which has seen a decline in manufacturing activity and offshore investment, according to the European Commission economic forecast.

Norway gained a competitive edge by moving away from oil-indexed contracts earlier than other exporters, instead linking the sale of most of its gas to spot prices. Russia has taken the opposite approach by sticking to oil-indexed deals.

In January, Norway’s Statoil changed its long-term contract price formula for LNG exports to Lithuania to bring the price closer to that of pipeline gas. The five-year contract, which is for 2.7 bcm of gas as LNG, had a price that was originally set at €27-30/MWh ($8.85-9.83/MMBtu). According to estimates, the price could fall by up to 25%, to €16-20/MWh.

Despite the record volumes delivered, Norway is cutting costs where it can. Statoil has said that between 1,100 and 1,500 permanent jobs will go by the end of 2016. The country is also freezing new investments on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS), which encompasses large areas of the North Sea, the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea. Spending on the NCS fell by 16% in 2015, to just under NOK 150 billion, and will continue to decline until 2019.

Analysts say the development of Barents Sea gas resources – which environmentalists have heavily opposed – now seems unlikely for the foreseeable future.

The industry has called for a change to tax and depreciation rates that dent the profitability of fields, but the Norwegian government has so far been reluctant to respond.

Analysts say this is mainly because Oslo has recognised the industry was somewhat inflated before the oil price drop and was in need of correction. The government is not expected to act unless oil prices remain low well into 2017 – and even then, any state action will likely be limited to opening up new acreage for exploration.

Nevertheless, the industry will benefit from lower exploration costs, which are expected to drop in 2016 as the low oil price sparks improvements in efficiency.

Four new fields came onstream in 2015, while six fields are being developed in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea, two in the Norwegian Sea and one in the Barents Sea, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. The agency expects to receive development plans for another three new fields this year.

Explorers drilled 41 wildcat wells and 15 appraisal wells in 2015, with overall exploration costs estimated at about NOK 33 billion. This exceeded previous forecasts that only 40 wells would be drilled. However, most of these wells were sidetrack wells with lower exploration costs. The number of exploration wells is expected to drop to 30 in 2016, with total exploration costs of NOK 22 billion.

Russia

Mix the low oil price environment with Western sanctions and the devaluation of the ruble and you have a cocktail for a crisis in Russian finances. With Russia’s economy contracting by 3.7% in 2015, according to official statistics, there could still be worse to come as prices remain low.

The United States-based Energy Information Administration estimated that hydrocarbons accounted for 68% of Russia’s exports in 2013. Crude oil and petroleum products made up 54%, while the remaining 14% was gas, which is also priced against oil when exported. Since then, the price of Brent has tumbled from more than $100 per barrel to around $30/bbl, deeply cutting into state budgets.

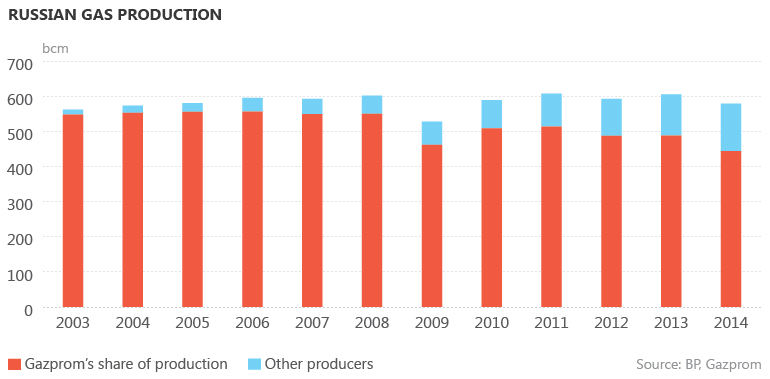

Gazprom’s production dropped to 418.5 bcm in 2015, a 5.7% fall from 2014 figures – which were already an all-time low. The state-run company originally forecast production of 487.4 bcm for the full-year 2015, but it was forced to repeatedly reel back on its projections.

Gazprom has spent recent years defending its use of oil indexation as the primary mechanism for pricing its gas exports. With the full consequences of the price drop now feeding through into lagged contract rates for European consumers, Gazprom is facing an export price of $180 per thousand cubic metres (Mcm: $4.90/MMBtu) in Q1 2016.

In comparison, the average export price charged to European consumers in 2014 was $346/Mcm. If the $180/Mcm price persists for 2016 as a whole, it would mark a fall in export revenue for Gazprom of 48%.

In response, Gazprom raised its cost-cutting goal to RUB 15 billion ($210 million) in December, shortly before issuing softer-than-expected losses for Q3 2015. The company benefits from the fact that most of its costs are denominated in rubles, while its revenues are in euros and dollars.

However, these factors are unlikely to last in the medium term, prompting officials to look at ways to mitigate the fall in oil revenue.

One quick response is further belt-tightening. Russia’s Energy Minister Alexander Novak said in January that companies should review investment plans and look at reducing costs. Novak held a meeting with oil and gas companies on 28 January to explore cost-reduction options.

"Since we have a market situation, companies should work primarily with their suppliers and contractors under long-term contracts to reduce their costs. For its part, the state must create conditions to encourage competition so that there are no monopolists on these markets," Novak said in Moscow in late January.

Another option being explored is the creation of financial instruments that would allow Russia to copy Mexico in hedging its oil production. Deputy Finance Minister Maxim Oreshkin said in January that, although such a policy remained at the theoretical stage, a goal for 2016 was to create the technical infrastructure for such an instrument to be launched if needed.

Qatar

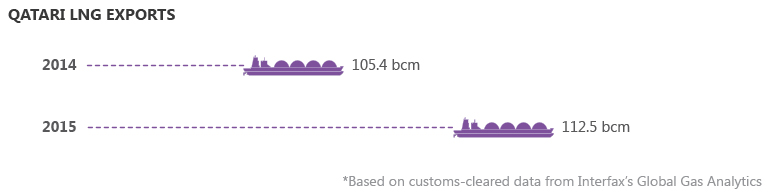

As the world’s largest LNG exporter, Qatar has been hit hard by the drop in global oil prices. Its response has been pragmatic: the country has shown it is willing to renegotiate long-term contracts to retain buyers and accept short-term contracts to sell its spare capacity. Meanwhile, Qatar’s government is slashing spending to help balance its books.

Much of Qatar’s LNG output is contracted under long-term agreements, a fact that has sheltered the country from the price drop to some extent. However, India’s state-owned Petronet LNG refused to take contracted Qatari gas when cheaper supplies became available. This brought Qatar’s RasGas to the negotiating table and convinced the company to reduce its prices rather than lose a key buyer.

Uncontracted LNG output and new trains at facilities run by Qatargas and RasGas helped Qatar’s LNG exporters to cash in while energy prices were high. RasGas was able to command $13-14/MMBtu from Asian buyers for five years before the oil price slump, helping the company to build up a comfortable surplus to help weather the storm.

However, Qatar’s producers are struggling to sell their spare output as many of their short-term contracts are expiring and they are unable to secure new long-term deals while the world’s energy markets are in flux.

Instead, Qatar has accepted that more flexible arrangements are necessary. “[Buyers] are looking at shorter and shorter terms, and some of them prefer to stick to the spot market until the market actually gets more stable,” Mohammed Saleh al-Sada, Qatar’s minister of energy and industry, said at a conference in London in January 2016.

Qatar will have more gas to sell once the Barzan field enters production later this year. The field, which is expected to produce up to 42 million cubic metres of gas per day (MMcm/d), was the last project to be sanctioned before Qatar imposed a moratorium on further developments.

Qatar has given no indication that it will scrap the moratorium. However, it still plans to increase gas exports to its neighbours via the Dolphin pipeline, two engineers from the project told Natural Gas Daily in January.

While the future of Qatar’s LNG business appears bleak, the country’s gas is still cheap to produce, and this works in the industry’s favour. Traditionally, Qatar was considered to have negative lifting costs because the costs of extraction were offset by liquids production, meaning the gas would basically be produced for free. Qatar can therefore justify continuing to export LNG even at low prices.

Even so, Qatar will still face a hole in its state budget created by its reliance on LNG exports. Around 90% of the government’s revenue comes from hydrocarbons, and the drop in oil prices means that, in 2016, Qatar will face its first budget deficit for 15 years.

Qatar is implementing a raft of cost-cutting measures in the energy sector and beyond. It hiked petrol prices on 14 January 2016 after raising electricity and water tariffs in 2015. It has also cut the budgets of some of its cultural projects and shut down the Al Jazeera America news service. Qatar’s leader Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani issued a decree merging some portfolios on 27 January, a move that has also been attributed to cutting costs.

Nigeria

Nigeria’s economy has been hit hard by the drop in oil prices. Oil sales account for roughly 70% of government revenue and, as the value of crude has sunk lower, so has the country’s currency. The naira hit a record low of 282 to the dollar on the unofficial market in January.

The shrinking budget will hamper President Muhammadu Buhari’s plan to reform the economy by building up a local manufacturing base, cutting imports and enforcing tighter controls on official forex flows.

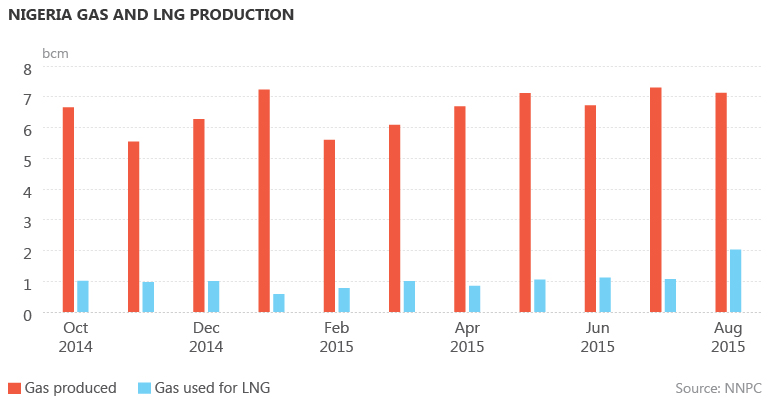

LNG exports have provided a crucial stream of revenue for Nigeria as the value of its oil sales has fallen. Exports accounted for around 44% of Nigeria’s 221 MMcm/d of gas production in the first nine months of 2015, according to figures from the World Bank. LNG sales came to 20 mt last year, just below Nigeria’s 22 mtpa nameplate capacity. Nigeria’s LNG contracts are linked to oil prices, so oil's fall has damaged revenues. However, Natural Gas Daily understands the project’s low breakeven price means the projects are still profitable if the oil price is above $30/bbl oil – and perhaps even lower.

However, despite plans to increase its export capacity, Nigeria looks unlikely to do so in the near term. French major Total withdrew from the proposed 10 mtpa Brass LNG plant late last year, adding to doubts about the project’s future. The facility will be expensive to construct, and as local customers are willing to pay at least $3/MMBtu for gas, supplying the domestic market looks increasingly attractive.

The government’s first response to the oil crisis has been to focus on reforming state-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. to tackle corruption and inefficiency. Management of the company has been restructured and tougher transparency and reporting standards have been enforced to stem revenue leakage. Further streamlining and reform of the company is expected via the Petroleum Investment Bill, which should be debated in Nigeria’s parliament later this year.

The government has also committed to addressing pipeline vandalism and crude theft, which is estimated to cost the country $6 billion per year. A total of 2,557 incidences of vandalism were recorded in the first 10 months of 2015, resulting in substantial value loss in terms of crude and other products. Eni had to declare force majeure on cargoes from Nigeria’s 22 mtpa capacity LNG plant in mid-December following an act of sabotage on the Ogoda-Brass pipeline.

Indonesia

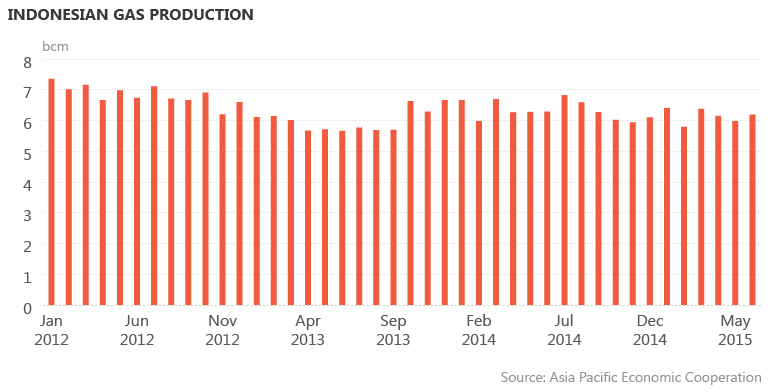

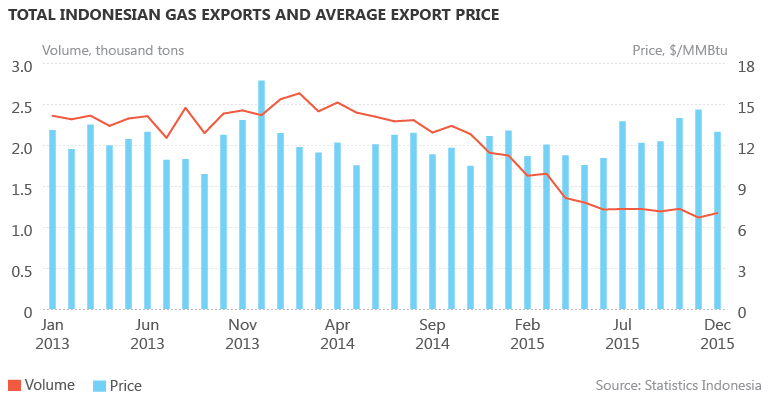

Pertamina, Indonesia’s state oil and gas company, is set to buck the global trend by increasing its capital expenditure this year despite low oil prices reducing revenues.

The company plans to increase capital expenditure by 20% in 2016, while cutting operational costs by 30% to streamline its organisation.

The company’s president, Dwi Soetjipto, announced that increasing capital expenditure is necessary because production is lagging demand and a period of low prices is the best time to invest in exploration.

The company plans to spend $5.31 billion in 2016 and has earmarked $3.8 billion, or 72%, for upstream projects.

However, this increase in spending is less dramatic than was planned before the drop in oil prices. Pertamina cut its four-year investment plan for the 2015-2018 period by 50% last year, to $25.8 billion.

Indonesia’s gas production is in decline as some of the country’s largest fields are maturing. Output from the Mahakam block, which produces around 25% of the country’s gas, is falling and is expected to be 34-37 MMcm/d in 2016 – below its 40 MMcm/d target. Work to maximise production from these fields is considered a priority.

With this in mind, Pertamina intends to reclaim expiring legacy production-sharing contracts operated by IOCs when they expire. The company will have first right of refusal for the blocks and aims to tighten its grip on the sector.

Pertamina will position itself as operator of the blocks, but it still wants strategic partners to help finance projects and transfer knowledge. Twenty-seven PSCs are set to expire in the next five years, representing around 30% of the country’s total production.

China

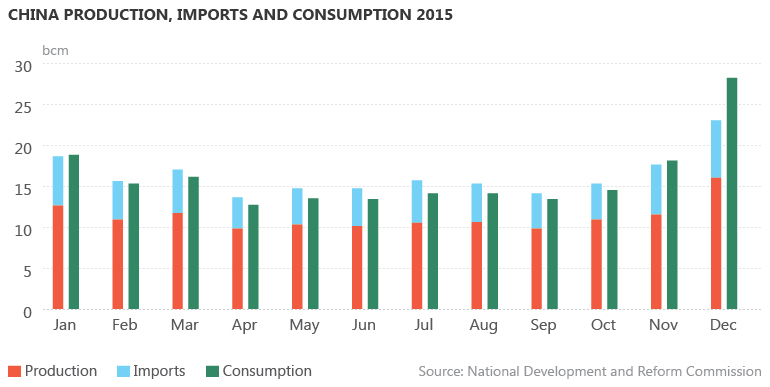

China’s gas output growth declined sharply in 2015, growing at its slowest pace in years as domestic demand for the fuel collapsed.

Chinese output expanded to 127.1 bcm last year, but this represented a year-on-year increase of just 2.9% – the slowest rise since 1998 – according to official statistics and China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC). The economy performed even worse, with GDP growth of 6.9% being the slowest in 25 years.

Gas production growth has been affected mainly by soft demand rather than the crash in oil prices. Consumption grew slower than the economy for a second consecutive year in 2015, rising by just 5.7% on an annual basis.

But low oil prices also forced state-owned CNPC and its fellow majors – not known for their capital discipline – into a rare round of belt-tightening to shore up their balance sheets.

The newfound focus on cost-cutting has continued this year. China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) said last month that it will trim its capital budget for the second successive year, reducing it by at least 11% in 2016 to less than RMB 60 billion ($9.1 billion) – its lowest level since 2012. CNOOC lowered capex in 2015 by a much steeper 37% from a year earlier.

The severity of the spending pullback by China’s oil majors has been reflected in the shale gas sector. The country spent several years working towards its first official production target in 2015, but efforts petered out after CNPC and Sinopec cut output to focus on the lower end of the cost curve.

The target of 6.5 bcm looks to have been missed by a wide margin, leaving China behind schedule in its efforts to copy the success of the United States in shale production.

Some companies, however, saw low oil prices as an opportunity to diversify their businesses. Low prices prompted Sinopec to accelerate a shift in its production mix from oil towards gas and to prioritise gas in future upstream investment.

“In the future, gas will be the main profit contributor in the company’s upstream. This gas business will represent the company’s future,” Sinopec’s management said.

The drop in oil prices dealt a blow to the development of an LNG economy in China as LNG use ground to a halt in road and river transport. Many would-be users of LNG shelved their plans to switch and slowed progress on LNG infrastructure – especially bunkering.

The government’s aim was to have more than 2% of China’s inland fleet running on LNG by the end of the 2015, equivalent to some 2,000 vessels. But only 15 LNG-powered ships were plying the country’s rivers at the end of last year.

China’s LNG truck production, meanwhile, slumped by 81% year on year in November, with the number of vehicles rolling off the manufacturing line in the first 11 months falling by 69% from 2014, according to government data.

United States

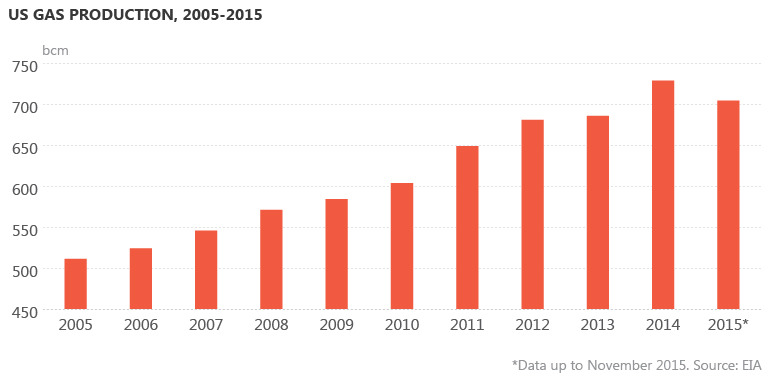

America’s oil and gas production has recorded five consecutive years of growth that have changed the global dynamics of supply and demand. The rise in domestic production in the United States reduced the need for the country to import oil, but the outlook for 2016 is gloomy. Production is forecast to increase only marginally, demand remains weak and an oversupplied market continues to affect prices – especially for US shale.

Shale producers have reaped the benefit of lower profit margins until now because of efficient and improving drilling and fracking techniques, which have reduced the time it takes to drill a well. But times have changed – the US West Texas Intermediate crude oil benchmark dipped below $30 per barrel in January, making it economically unviable to drill new wells. Baker Hughes – the bellwether for the US oil and gas drilling industry – reported that the number of active oil rigs for the week ending 8 January fell by 20, to 516 – just one-third of the 1,421 rigs that were operating during the same period in 2014. The oil services provider estimates the number of rigs in use will decline by a further 30% if oil prices do not recover this year.

Financial exposure is a further sign of future constraint. North American gas companies have hedged less than a fifth of their production volumes for 2016 against oil and gas price fluctuations. This will leave them exposed to lower prices this year and next.

Over the past 18 months, many large and small US energy companies have reduced costs, refinanced or restructured their organisations, made job cuts or filed for bankruptcy protection – a trend expected to continue during 2016. Forty US and Canadian energy companies have also filed for bankruptcy over the past year and a half. The US energy industry is likely to see more acquisitions and mergers as companies go bust or sell assets. The three top credit rating agencies – Moody's, Standard & Poor's and Fitch Ratings – have all forecast difficult financial times ahead for energy companies.

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) projects US gas output growth will slow to 0.7% in 2016 as low gas prices and declining rig activity begin to affect production. Production growth is forecast to marginally recover in 2017, to 1.8%, as prices increase and demand grows from industrial users and LNG exporters. The average spot price at the Henry Hub for December 2015 was $1.93/MMBtu – the lowest monthly average since March 1999, according to the US EIA. The agency has forecast Henry Hub spot prices will rise to an average of $2.65/MMBtu in 2016, largely as a result of increased industrial demand.

Environmental reforms applying stringent carbon emissions targets will be a plus for the US gas industry. The Clean Power Plan, introduced by President Barack Obama and the US Environmental Protection Agency, will see demand for gas rise to replace coal-fired power generation in the next decade. However, it will not be enough in the near term to soak up excess gas production. The EIA forecasts US gas consumption will average 2.17 bcm/d this year – an increase of only 31.2 MMcm/d compared with 2.14 bcm/d in 2015.

Bolivia

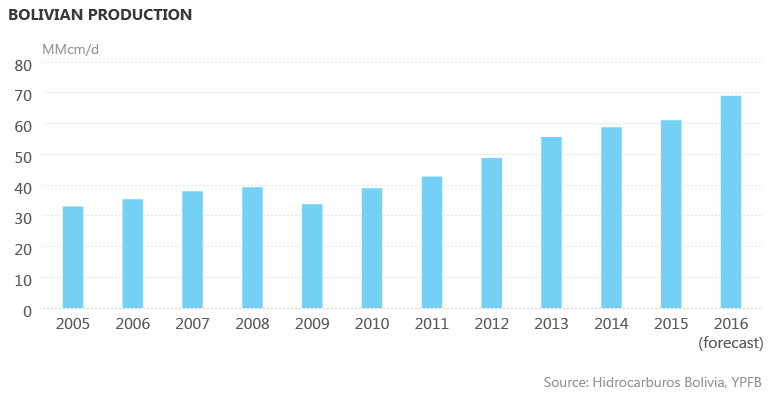

Bolivia, the breadbasket of the Southern Cone gas market, is hoping to ride out the bear market by pedalling harder. Lower crude prices have dented the Bolivian economy, with the country’s annual hydrocarbon revenues down by more than 31% in 2015, to $3.77 billion. Gas accounts for roughly 45% of Bolivia’s exports by value.

La Paz has decided to boost gas production from the country’s existing fields to maintain revenues in 2016. Bolivian Vice President Álvaro García Linera told local press in January the country would lift its output by 13% this year, to 69 million cubic metres per day (MMcm/d).

Despite the ‘extra’ output, state-run company YPFB has forecast that oil and gas revenues will be flat year on year in 2016. However, the forecast depends on an average oil price of $45 per barrel, and crude has averaged $30/bbl so far in 2016.

La Paz may also struggle to find a market for the extra output. Bolivia exports around 45 MMcm/d to Argentina and Brazil, which constitutes the majority of its production. However, Argentina’s demand is sluggish and Brazil has successfully increased its domestic production in recent years.

The Bolivian export tariff is derived from a basket of fuel oil and diesel prices, with the West Texas Intermediate benchmark used as the reference point. La Paz has been pushing for a ‘fair’ price for its exports rather than one linked to crude. However, it has limited bargaining power in this environment.

Bolivia exported gas to Argentina for $4.8/MMBtu and to Brazil for $4.3/MMBtu in Q4 2015, down from $9.9/MMBtu and $8.4/MMBtu respectively in Q4 2014. The prices are renegotiated every quarter. Interfax estimates they will be similar or slightly lower in Q1 2016.