Are LNG benchmarks still relevant?

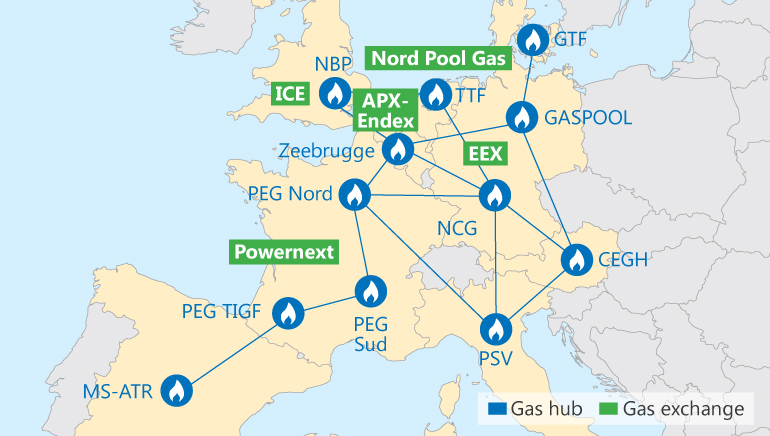

European gas hubs and gas exchanges.

European gas hubs and gas exchanges.

On the one hand, gas is a commodity with a price defined by regional supply-demand pressures, such as the weather, local production and storage issues, and energy policy initiatives. Unlike oil – the bulk of which can be sold anywhere in the world – gas has historically been tradeable by pipeline within tightly defined geographical areas or as LNG from port to port. However, it has not traditionally been traded as a global commodity that can be easily arbitraged between regions.

The recent growth of the LNG market was expected to change all that. Destination restrictions have been eased on most of the cargoes sold from the new plants in Australia, and the growing share of LNG from the United States in export markets will add to the availability of spot volumes over the next five years. More than half the LNG that will be exported from the US will be held by portfolio players or Japanese companies that have similar flexibility in how they sell cargoes. The emergence of a global LNG market has become a real prospect, reinforcing hopes that benchmarks for the fuel will gain traction.

While US volumes are typically linked to the Henry Hub price, more than two-thirds of global LNG supply remains indexed to oil. Although the LNG market is switching away from oil indexation, it is doing so at a slow pace. Moreover, LNG benchmarks have been slow to emerge. When LNG outside the US is indexed to gas, the UK’s NBP hub or continental prices at the TTF in the Netherlands or Zeebrugge in Belgium are typically used as reference points.

There have been several attempts to establish specific LNG pricing benchmarks, including products offered by Japan’s over-the-counter (OTC) exchange, Shanghai’s oil and gas exchange, and Singapore’s SGX, but these have failed to gain momentum. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange has also supported the concept of non-deliverable contracts for LNG.

Japan, the world’s biggest LNG importer, has been promoting itself both as a location for price benchmarking and as a trading hub to compete with Singapore, the historical role of which as an oil trading centre has made it an attractive base for LNG traders. The Gwangyang terminal in South Korea has also been touted as a possible location for price benchmarking and potentially also for cargo re-exports.

Among the price reporting agencies, Platts offers the Japan Korea Marker, while ICIS has a number of Asian indices that include delivered ex-ship spot assessments and the East Asia Index. Petroleum Argus also offers gas price assessments and expanded its Asian LNG assessments shortly after the Fukushima incident.

However, despite all the talk none of the LNG contracts on offer has gained significant momentum as a pricing reference point, despite top-down governmental support for the various exchange-based offerings. A few sporadic swap deals have been concluded on price reporting agency assessments, but the volumes involved were of a different order to those traded in oil swap markets. None of the exchange-based or OTC offerings show signs of taking off yet, despite frequent media initiatives to promote them.

Instead, LNG producers appear increasingly relaxed with the concept of using natural hubs in pricing LNG. Growing liquidity in the major European gas hubs has gradually eroded fears that these markets can be manipulated and, although they remain volatile and responsive to regional factors, this can be managed either by hedging or by using extended pricing periods or pricing periods with lags.

Turning point

Europe’s role as a potential sink for US LNG means European gas prices will be increasingly influenced by global prices, even if the typical flow of LNG from the US is to higher-value markets in Latin America, the Middle East and Asia.

This could mark a significant turning point in how the market thinks of LNG pricing. The spike in Japanese LNG demand after the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident led to a tight market in which gas prices were sharply differentiated by geographical region. Typically, while Henry Hub prices languished at $2-4/MMBtu, European prices fluctuated between $7-11/MMBtu and Asian LNG markets were much higher, at $13-20/MMBtu depending on the season. The so-called ‘Asian premium’ led to prices that often reflected strong premiums to the arbitrage value from re-export locations such as Europe, prompting Japanese buyers to try to diversify the basis of their pricing away from oil indexation to gas-on-gas pricing.

This divergence of prices was largely caused by the bulk of LNG being oil indexed while prices at trading hubs reflected regional gas fundamentals. The simultaneous plunge in global oil and gas prices in 2015 resulted in closer regional convergence among gas prices. If oil prices were to rebound, a two-tier market between oil-indexed and hub-linked gas could re-emerge. Linking LNG pricing to gas prices at the trading hubs would potentially eliminate this risk.