Oil and gas prices may go their separate ways

The commissioning cargo at Gorgon LNG. Large amounts of Australian supply coming onstream will keep Asian prices low. (Chevron)

The commissioning cargo at Gorgon LNG. Large amounts of Australian supply coming onstream will keep Asian prices low. (Chevron)

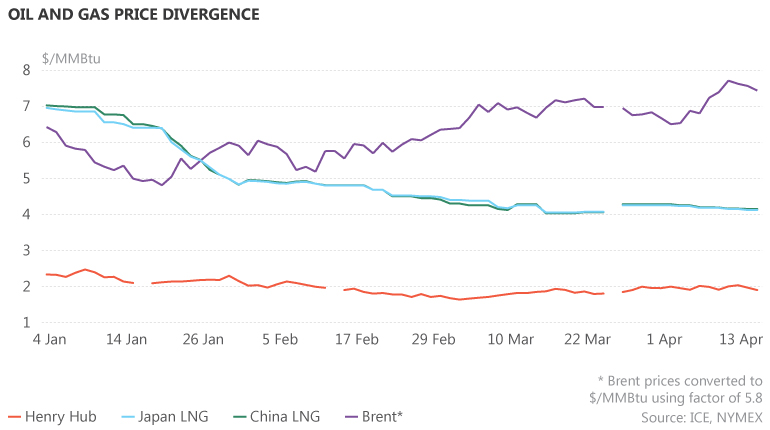

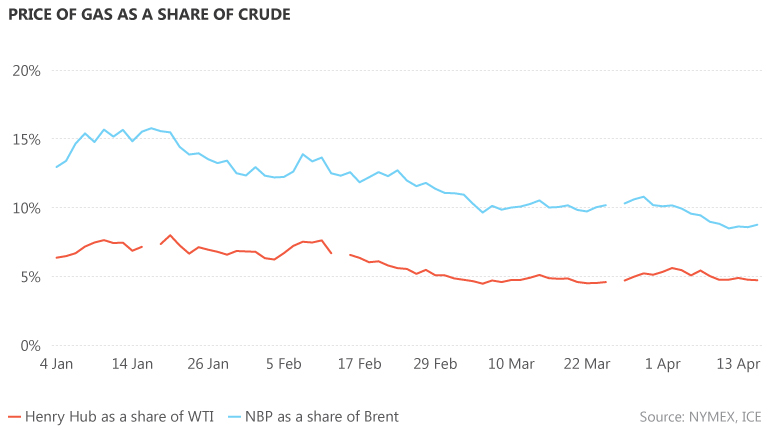

The North Sea Brent price has rallied from the lows seen in January, but gas prices have been stymied by surplus LNG from plants in the United States and Asia. The problem has been compounded by a mild winter that has left countries with comfortable gas stocks at the end of the peak winter consumption period.

ICE Brent futures have risen from below $27 per barrel in January to recent peaks of around $44.69/bbl. Although prices dropped sharply after the failed meeting between OPEC and non-OPEC countries in Doha on 17 April, they quickly recovered from around $38/bbl to above $42/bbl.

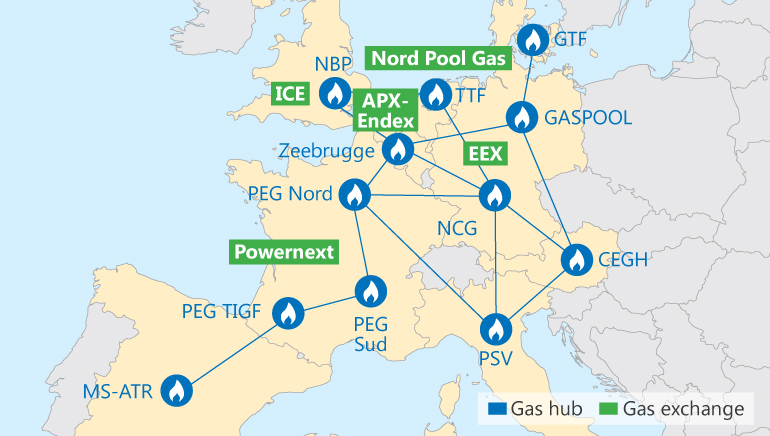

In contrast, futures at the UK’s NBP hub have dropped relentlessly, from 35 p/th ($5.04/MMBtu) at the start of 2016 to around 26.5 p/th. US Henry Hub futures have also fared badly – spot prices dropped to $1.47/MMBtu in March while futures plunged to a low of $1.61/MMBtu, the lowest level since 1998.

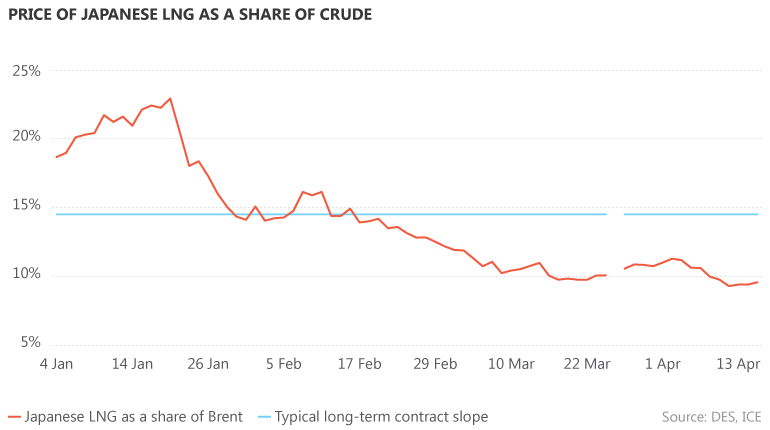

LNG prices have fared even worse. Delivered ex-ship spot prices in China and Japan have dropped from around $7/MMBtu at the start of the year to around $4/MMBtu currently, and there is limited prospect for recovery as Asian markets enter spring. Although a hot summer in northern Asia could reverse the downward trend in LNG prices, any upside will be limited given the new supplies due from large Australian plants such as Gorgon.

Conversely, the oil market is gradually rebalancing. US production dropped below 9 million barrels per day in early April as the price slump hit shale producers. The speed with which futures prices recovered after the Doha meeting suggests an underlying easing of the supply pressures. Oil production typically declines by 2-8% per year as fields become depleted, while consumption is growing at 1.2-1.3 million b/d per year because of continued strong demand growth for liquid fuels in Asia. The price relationship between the two commodities is important because it can determine trends in fuel substitution – for instance, between oil-derived fuels such as diesel in transport and potential competitors such as LNG.

The recent widening price spread between the two fuels partly reflects the lag in oil-indexed long-term contracts for natural gas and LNG. These typically trail the spot price for the type of oil used in the indexation – which includes crude, diesel and heavy fuel oil – by three to nine months, depending on the region and customer.

In the past, a strong oil price rally has typically seen gas contract prices catch up after a few months. However, with the advent of US LNG exports tied to Henry Hub prices, the traditional relationship between the two fuels may break down.

The four-decade-old US ban on crude oil exports was lifted last year, so any recovery in the global oil price would quickly filter through into improved shale oil prices. In the past, shale gas production has been subsidised by revenues from the liquid streams (condensates and crude oil) derived from fracking.

Ironically, therefore, while low prices have hit US shale gas as well as shale oil production, any recovery in oil prices may result in more gas being available for US domestic consumption or for export as LNG.

Because US LNG exports are not indexed to oil prices, they could potentially act as a cap for spot gas and LNG prices if the oil price recovers. This would further widen the gap between oil and gas prices, putting pressure on suppliers to offer more flexible terms to contract holders – particularly given that a number of long-term gas contracts are coming up for renewal soon.