Upstream cuts create potential for supply shock

When ExxonMobil convenes its annual shareholders’ meeting on Wednesday, it will be the first time in 65 years it will do so without the company holding an AAA credit rating from Standard and Poor’s (S&P). The ratings agency downgraded the US oil major from AAA to AA+ last month, leaving Microsoft and Johnson & Johnson as the only US companies with AAA status from S&P. Moody’s reaffirmed its AAA rating for Exxon in February but switched its outlook to negative.

S&P cut Exxon’s credit rating because the company’s debt has risen while oil and gas prices have stayed too low for too long. It estimated Exxon’s cash-flow-to-debt ratio would remain below the level expected for an AAA rating until 2018. S&P said Exxon’s debt level had more than doubled in recent years, in part reflecting high capital spending on major projects while commodity prices were high. While Exxon says the company’s financial philosophy and prudent management of its balance sheet have not changed, S&P pointed out maintaining production and replacing reserves will ultimately require even more spending.

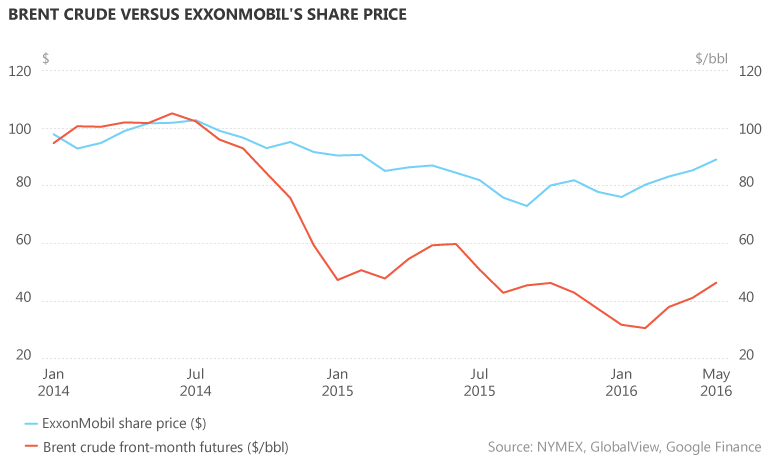

Exxon, like all other oil and gas companies, has made stringent efforts to cut spending during the downturn, which has knocked 55-60% off the value of crude oil and natural gas since mid-2014.

Nevertheless, the downgrade reflects a difficulty that all oil companies face: finding oil costs a lot of money and financing has become very difficult to find.

Exxon is not alone in its troubles. Oil and gas majors around the world are cutting investment even if it means reserve-replacement ratios and reserve-to-production ratios suffer.

Against the flow

Investing counter-cyclically in future flows of oil and gas makes perfect sense to veterans of previous price downturns. Not only are asset values depressed, rig rates have also plummeted and oil services firms have cut their fees to the bone. Purchasing distressed acreage held by overburdened independents or shale producers seems a no-brainer to many of those who experienced the price declines of 1986 and 1998.

But the banks’ fingers are still scorched from the 2008 credit crunch, and regulation requiring ever-higher capital adequacy makes discretionary lending difficult – particularly when the value of the collateral held against existing loans has been shrunk by the price collapse. In most case, banks will come up with refinancing options when needed for existing clients, if not only to avoid the messy outcome of liquidation. But they are reluctant to write new loans to fund exploration and development.

This problem is exacerbated by the fact that, as oil and gas prices decline, the reserve base is naturally reduced because the definition of reserves depends on the commercial viability of their development. Exxon’s reserve additions in 2015 replaced only 67% of production, the first time in 22 years the major has failed to find more hydrocarbons than it produced. Although 1.9 billion barrels of total liquids were added, proven gas reserves were reduced by 834 million barrels of oil equivalent, mainly in the US, reflecting the change in gas prices. The company said it still expects this gas to be developed and booked as proven reserves in the future.

While private equity funds are awash with capital, they also appear reluctant to invest in upstream oil and gas. High capital expenditure and operating costs required for upstream projects mean returns on investments are unattractive compared with competing – and less capital-intensive – industries, such as biotech. Meanwhile, renewable energy companies are benefiting from lower costs, government support and new sources of finance such as green bonds.

This leaves oil companies between a rock and a hard place. Capex budgets have been slashed, opex is being reined in wherever possible, and if the cupboard is not completely bare, any leftovers are typically being distributed to shareholders rather than invested in the upstream. Staff with decades of experience have left the industry in droves, threatening a skills shortage in the years ahead.

Supply shock

All of this is potentially bad news for consumers. There are grounds to believe the oil price spike to $150 per barrel in 2008 resulted from low investment when oil prices were mired at below $10/bbl a decade earlier. Oil and gas exploration and development requires long lead times. While counter-cyclical investment now would potentially avoid an oil price shock at the end of the decade, there is a real risk lack of financing will defer the investment needed to meet future oil and gas demand growth until prices have improved.

The oil market is widely expected to rebalance between now and 2018, with the gas market likely to follow suit sometime after 2020. The market should be anticipating future shortages and using them as a cue to action now, but so far the futures market is failing to give these signals. There is therefore the risk of a potentially damaging supply shock in the future.