LNG supply – the outlook from MJMEnergy

LNG Barcelona Knutsen loading up at Peru's Pampa Melchorita liquefaction facility. (Repsol)

LNG Barcelona Knutsen loading up at Peru's Pampa Melchorita liquefaction facility. (Repsol)

MJMEnergy’s recently released LNG Supply Handbook provides a comprehensive overview of the outlook for global LNG supply until 2035. Written by LNG experts, the book contains detailed analysis of 28 current and future LNG supplier countries. GGA spoke to co-author Nick White for his view on what will shape the global outlook for future LNG supplies and trade.

GGA: New supply from Australia, the United States and elsewhere will be key to growth in the global supply of LNG between now and 2035. What effect are low oil prices having on the outlook for new supply from these countries?

Nick White: There is already a huge amount of LNG liquefaction capacity under construction in Australia. There are seven projects planned with a total capacity of 61.8 mtpa – including Queensland Curtis LNG, which is already part operational. These projects are mostly well advanced and likely to be completed, leading to significant new supplies of LNG on the world market by 2020.

However, the economics of the projects will be much more challenging at low oil and LNG prices. This will make it much harder for new projects or project expansions to reach FID. So Australia’s LNG supply will grow rapidly over the next four years, but then slowly – if at all – later on. Although Australia has huge gas resources, in many cases new production facilities are required to exploit them – so unless prices rise, further expansion is likely to be limited. Already a number of planned projects have been cancelled or postponed.

In the US, low oil and gas prices are having a more complicated effect. In many cases, new projects are conversions of existing LNG regasification terminals. Therefore, capital costs tend to be lower, and gas supply for liquefaction is coming from existing production and a liquid gas spot market. Low oil prices tend to lead to low gas prices in the US – where gas is currently languishing below $3/MMBtu. This should make US LNG competitive with international oil-indexed gas and LNG prices, even once the costs of liquefying and shipping to Europe, South America or possibly Asia are included.

In addition, liquefaction tolling arrangements reduce the risk for developers, while buyers may still like to take advantage of low US prices. The key challenge for new US projects now is the cost of a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission permit and the associated environmental review – which is estimated to be up to $100 million. While low oil prices may make it harder for US projects to finance this process, there are still prospects for additional US supply through the 2020s, even in a low oil price environment.

GGA: Can you explain the shift in where supply will come from and the impact this could have on trade?

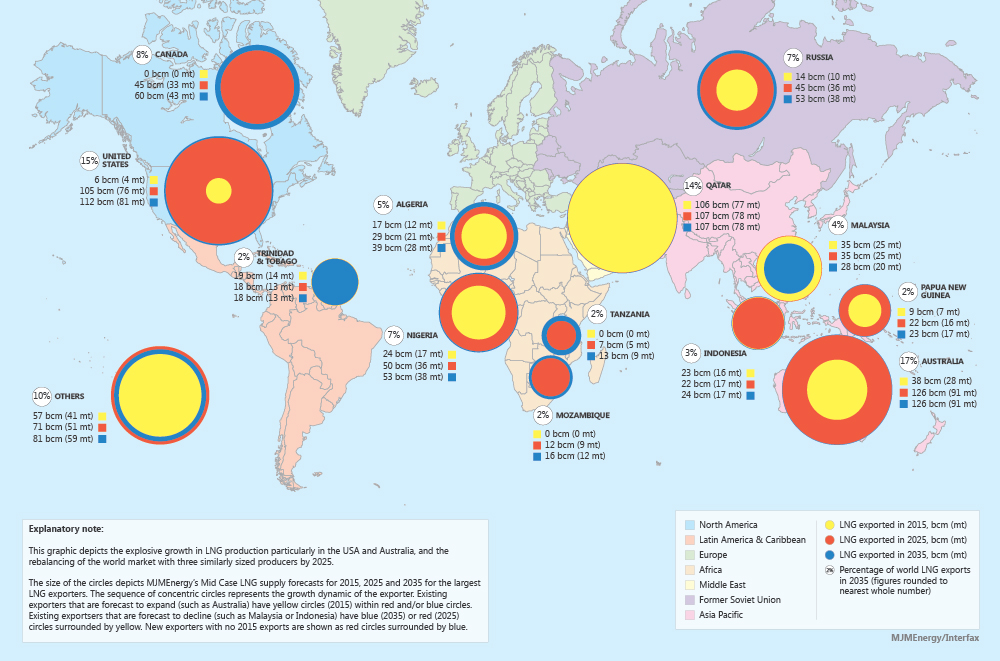

NW: Qatar is currently the dominant world LNG exporter with 31% of world supply in 2014, while four others – Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Nigeria – each supply approximately 10%. In our mid-case scenario Australia overtakes Qatar by 2020, followed by the US by 2030, leading to these three suppliers each contributing 14-17% of global supply. New supplies – particularly from the US – are less likely to be tied into long-term contract destinations, and there will be more flexibility in supply routes.

In addition, the growth of Australian and US supplies (as well as potentially Canadian, Russian and East African LNG) will somewhat change Qatar’s role. Where recently it has occupied a key central position between world markets, able to diversify its risk by selling all over the world, it may find itself more disadvantaged in comparison with Australia in Asian markets and the US in European and South American markets.

GGA: There are three demand scenarios in your book, with global demand in the mid-case being around 716 billion cubic metres in 2035 while the high- and low-case scenarios forecast 940 bcm and 540 bcm respectively. Can you explain some of the key assumptions driving the mid-case scenario?

NW: For the mid-case, we used [information service] Cedigaz’s existing global LNG demand forecast, while developing our own high and low cases based on a range of other forecasts and our own analysis. Forecasting LNG demand is challenging, as in most cases it is fungible with pipeline gas. However, key assumptions underlying the mid-case include the continued growth of energy demand, linked to the rising global population and economic growth. Aside from general socioeconomic issues, specific LNG drivers include interactions with generation from nuclear power and renewables, geopolitics and pipeline security issues, and decisions regarding the role of gas in a low-carbon future.

GGA: One conclusion from the Handbook is that LNG supplies could overtake pipeline supplies by 2035. How likely is it that this will happen?

NW: Currently, about 33% of the gas traded internationally is delivered as LNG. This percentage will increase to at least above 40% by the late 2020s. Whether it gets above 50% by 2035 is more uncertain and will depend both on LNG and pipeline developments – for example, the recent huge pipeline deals between Russia and China. It is most likely that LNG will account for just under half of internationally traded gas.

GGA: The Handbook covers changes in the commercial structures of contracts. How do you see levels of flexibility and the balance between long-term contracts and spot trade changing over the next 20 years?

NW: The level of flexibility is going to increase – indeed, I would expect almost all long-term contracts signed from now onwards to have some degree of destination flexibility in them. Spot trading volumes are also likely to keep increasing, not only because of new facilities where not all capacity has been sold in advance, but also because of older facilities where initial contracts are coming to an end and the sellers may not wish, or be able, to sign replacement long-term contracts.

In addition, an increasing number of new long-term contracts are likely to be on a portfolio basis (where the seller agrees to supply LNG but doesn’t specify the source) or a tolling basis (where the buyer purchases liquefaction capacity but is responsible for sourcing the gas and has complete destination flexibility). However, there will still be significant volumes of traditional long-term contract LNG for the next 10-20 years under existing contracts.

GGA: How essential will smaller-scale and FLNG technology be to the growth of LNG supply until 2035?

NW: This is an area of uncertainty as the first FLNG facilities have not yet become operational (but probably will be later this year) and small-scale LNG is currently on a very small scale.

However, the prospects are good. In particular, although the Prelude FLNG project is looking like being hugely expensive, smaller FLNG projects could reduce costs in many cases and increase the ability to exploit challenging offshore reserves. Overall, the impact is likely to be comparatively small – most FLNG and small-scale LNG projects are below 2mtpa – but it does open up new areas and possibilities.

GGA: What are the key challenges facing LNG suppliers between now and 2035?

NW: Securing demand to meet growing supplies is a big issue. LNG suppliers are facing the challenge of low prices over the next 5-10 years in particular and are likely to face additional challenges of greater supply competition, while China’s emerging economic slowdown and pipeline supply deals with Russia may drag on LNG demand growth. The growth of Australia and especially the emergence of the US as large LNG suppliers will change contract structures – with greater flexibility, and more portfolio and tolling arrangements.

Short-term trading is likely to increase in importance, although trade may also regionalise again, with global interactions being a lower percentage of spot trading. Suppliers may have to develop more flexible contracts – and take a greater share of the risk – to secure buyers, particularly for long-term contracts. However, new opportunities are emerging. In particular, FLNG and small-scale LNG allow new smaller players to enter the market, and the growth of LNG as a transport fuel could see large new markets develop. Overall, the LNG supply industry is becoming more complex and fragmented, and is no longer the province of a small number of large buyers and sellers.

Nick White is principal consultant at MJMEnergy and currently heads up MJMEnergy’s training business, where he is Course Director on the LNG Economics and Markets course. Nick is also the editor of MJMEnergy’s LNG Today report, and is co-author of a number of other energy market reports, including Liberalising Gas Markets in Europe, Convergence in the Global Gas and Power Industry, the Long-term Capacity Auctions, and LNG as Transport Fuel.

The MJMEnergy LNG Supply Handbook is priced at £950 plus shipping for hardcopy and secure pdf download. Use coupon code IFAX20 before the end of December 2015 for a 20% discount when placing your order. You can order online: www.mjmenergy.com/publishing/lngsh or email: [email protected].