The UK gas sector will face short- and medium-term challenges and opportunities as the UK negotiates its exit from the EU.

The UK gas sector will face short- and medium-term challenges and opportunities as the UK negotiates its exit from the EU.

What to expect now Article 50 has been triggered

The UK is facing at least two years of negotiations with the EU on the terms of leaving and its future relationship with the union. At this point, the outcome of the negotiations is impossible to predict. It has been suggested Brexit could fundamentally change the EU into a more flexible union; it has also been suggested it could make the EU more protectionist. We consider the possibility the relationship between the two sides will break down is remote, as the potential is mitigated by mutual vested interests.

Brexit adds to the challenge of the lower oil price environment

Over the last two years, the UK gas industry has faced turbulence linked to the collapse in the global price of crude oil. Total revenues across the UK oil and gas supply chain fell by 10% in 2015, with a further fall of 21% estimated for 2016 – taking the market to below £30 billion for the first time since 2010. The UK’s decision to leave the EU has added another dimension to this already challenging environment.

There are three main concerns for the industry:

- Uncertainty over the outcome of the Brexit negotiations;

- The loss of the UK’s ability to influence EU policy; and

- The distraction the process provides to the government’s usual business.

Overall, the industry has benefited from the devaluation of sterling, and further opportunities may arise during the Brexit negotiations. However, the vote has unsettled the business community as uncertainty is hanging over what kind of deal the UK will negotiate. EU officials recognise a transition deal will rest partly on a shared goal for future relations, yet they perceive the framework of a trade relationship as being more of a political aspiration than the kind of legally binding settlement pursued by London.

For this reason, businesses are looking for a quick solution to shorten the period of uncertainty. In recognition of the importance of providing some clarity, the government pledged in its February 2017 white paper on Brexit to introduce the Great Repeal Bill. The bill, if passed by Parliament, will convert existing EU law into domestic law.

With most of the UK gas industry’s upstream operations located in Scottish territorial waters, the position of Scotland in a post-Brexit environment will be critical to the industry’s future. However, the potential independence of Scotland is a separate issue, viewed by the industry as a factor affecting post-Brexit decision-making.

An overview of the UK gas industry under a hard Brexit

Future gas flows

WTO customs and tariffs will apply. Peak-shaving flows and imports from the EU will be reduced while domestic demand continues to shrink.

Production from the UKCS will be stabilised as a result of higher investment encouraged by more attractive incentives, which will reduce further requirements.

LNG imports are likely to increase as the fuel becomes more competitive against EU gas sources in the UK market.

Investment in the UKCS

International upstream companies whose earnings are mostly in US dollars will invest in the UKCS if the tax regime, decommissioning relief scheme and other investment incentives are in place and endorsed by the government.

This is likely to boost domestic gas production. On the other hand, the UK is likely to leave the EIB, which may prevent EIB infrastructure-funded projects from being built in the UK.

Domestic gas prices

Assuming increased reliance on US LNG, gas prices are likely to be increasingly influenced by Henry Hub gas prices denominated in US dollars.

The lower value of sterling, combined with the impact of this change on European hubs, would mean higher domestic prices.

Higher prices will be detrimental to demand from both household and business customers. Gas used in power generation could also be curtailed.

Hiring labour and services

The expected strict restrictions on immigration may hamper recruitment of professional services and labour from abroad. If this occurs, it could endanger efficient operation of the industry.

Consequently, additional education and training schemes will be required for domestic resources. This could provide an opportunity to create new companies to provide these services.

Exchange rate

Hard Brexit would mean the continuation of a suppressed pound value in the medium term if the expected slowdown in economic growth occurs.

Access to Europe

The UK will lose its membership of ACER and other EU institutions. This will reduce the UK’s ability to influence EU policy development.

WTO customs and tariffs may apply, which could hinder trade as prices would be inflated by additional duties. Companies wanting to access the EU may consider relocating to the Continent.

Upstream margins

Hard Brexit would mean the continuation of a suppressed pound value in the medium term if the expected slowdown in economic growth occurs.

Are we heading for a hard Brexit?

The prime minister’s statement on 17 January this year and the subsequent government white paper suggested the country was heading for a ‘hard’ Brexit – a view reinforced by May’s statement that the UK would rather leave negotiations without a deal than take what it considered to be a bad deal. However, her letter invoking Article 50 suggested a more conciliatory tone. The most likely outcome of the negotiations, and their impact on the gas industry, is far from clear at present.

A hard Brexit implies the UK’s trading relationship with the EU would be governed by World Trade Organization (WTO) conventions, customs and tariffs. This would have a significant impact on several areas:

- Future gas flows to and from the EU, including Ireland;

- Investment in the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS);

- Domestic gas prices;

- Exchange rates; and

- Other factors, such as the hiring of labour and professional services.

However, it is possible an arrangement comparable to the Norwegian model (in which Norway can export its gas to the EU and is bound by EU regulations but has no ability to influence those regulations) or the Swiss model (which comprises a series of complex bilateral deals) could be adopted at the end of the negotiations. It is considered that both models would soften a hard Brexit.

British gas industry is robust as EU plays a minor role

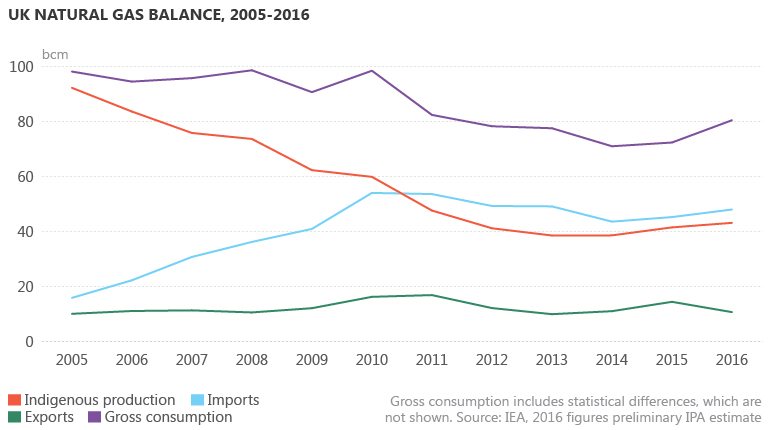

Across the value chain, the UK gas industry looks less vulnerable to the outcome of the Brexit negotiations than many other industries. This is because UK gas supplies are mainly sourced from the country’s own reserves. Domestic fields supplied 54% of UK demand in 2016, while 46% was imported either via pipeline from Norway (providing 65% of imports) or from countries such as Qatar as LNG (amounting to 24%). Only 12% of UK gas imports were sourced from the EU in 2016.

In the long term, the UK is expected to source increasing amounts of its gas as LNG from non-EU countries, such as the United States, or via pipeline. The UK has an abundant import capacity that is largely underutilised, but the question is whether alternative imports would be in the form of LNG or as pipeline gas from Norway or Russia (via mainland Europe). The UK has frequently exported gas during periods of peak demand in Continental Europe and is the primary source of gas to Ireland, which will remain part of the EU.

The UK has always had control of its energy policy and fuel mix, as Brussels has been much more concerned with building integrated European gas infrastructure and Projects of Common Interest. This is another area where Brexit will have only a limited impact, since most of the connections with the Continent are already in place and are largely underutilised. However, to ensure the NBP remains liquid, the UK needs to align its market to European hubs closely enough to encourage sufficient participation to ensure the market sends the right price signals.

The current trading arrangements help to ensure lower prices and improve security of supply for both sides by improving the efficiency and reliability of interconnector flows. The worst-case scenario is isolation for the UK, which would harm gas market liquidity and could push prices up. The Brexit white paper clearly states the UK will seek a solution that will avoid disruption to energy flows to Ireland and Continental Europe. However, saying Brexit will have a limited effect on the gas market and gas supplies does not mean the UK gas industry will be unaffected by the leaving process. One interesting factor could be the potential for a separate UK/US trade agreement, but the likelihood of preferential rates for LNG imports from the US is quite low. Despite the possibility of a trade deal with the US, LNG exporting companies are unlikely to cut their prices to the UK if they can get a premium for their supplies in Northeast Asia. The international competition and convergence of LNG prices across the world will keep prices at international levels for the UK post Brexit.

How will Brexit impact the UKCS investment?

One of the gas industry’s most important concerns is ensuring the UK continues to be an attractive place for investment in the post-Brexit era. In practice, this will depend on a combination of economic and policy-related factors.

The stabilisation of UKCS gas production and improvements in efficiency have been attributed to the surge in investment in the industry seen between 2010 and 2014, the results of which are only being seen now (see UKCS Oil & Gas Capital Expenditure, 2005-2017). This is considered to have been driven mainly by changes in oil and gas prices and exchange rate movements. There are seven larger gas fields being developed in the UK, four of which (Culzean, Edradour, Glenlivet and Harrier) are expected to come onstream between 2017 and 2019. The commissioning of the other three fields (Tolmount, Fram and Arran) has been put on hold, not because of Brexit but as a result of oil price developments. There is no evidence companies have withdrawn or postponed their investment in the UKCS because of Brexit.

In addition to being influenced by oil prices, investors require policy certainty: they need to be sure the government recognises that the UK’s oil and gas tax regime must be predictable and internationally competitive. Investors were reassured by the confirmation in September 2016 that the British government still plans to cut corporation tax to 17% by April 2020 (compared with an EU average of around 24%). A raft of measures was also introduced in April 2016 to boost the UK’s oil and gas industry. Brexit could provide the government with greater flexibility when setting commercial terms and taxation levels. However, there are concerns about whether the government will have the will or the time to spend on this matter as it is likely to be focused on wider negotiations.

One area where Brexit could have a significant impact on investment is through the finance provided to the sector by the European Investment Bank (EIB). Once the UK is no longer a member of the EU, the terms and conditions attached to loans from the EIB are likely to deteriorate. Although there are many other sources of capital, the UK industry’s inability to benefit from the EIB’s preferential terms will increase costs.

In aggregate, we consider that oil prices are likely to remain the most important determinant of investment in the UKCS.

Influences on future gas prices

International commodity prices will continue to determine the success of the industry. However, gas markets are still regional in nature and gas prices also respond to factors unrelated to global oil markets – such as weather-related seasonality in demand, storage capacity utilisation, LNG investment cycles, and the strategies of a few major gas exporters. Nevertheless, oil will continue to influence European gas prices, in particular because of the inclusion of the oil price in both Asian LNG term contracts and in a – albeit diminishing – number of European pipeline contracts. And even if the influence of oil prices on NBP price formation gradually diminishes, the impact of US Henry Hub prices will become a factor following the build-up of US LNG exports to the Atlantic Basin. Uncontracted LNG from the US will be available to UK and European hub markets, presenting more arbitrage opportunities between the Henry Hub and the NBP/TTF markets. Nevertheless, supply from Russia will compete with LNG from the US and elsewhere. Russia has large surplus volumes, however, if gas prices of European hubs recover then there will be an opportunity to export more US LNG to Europe.

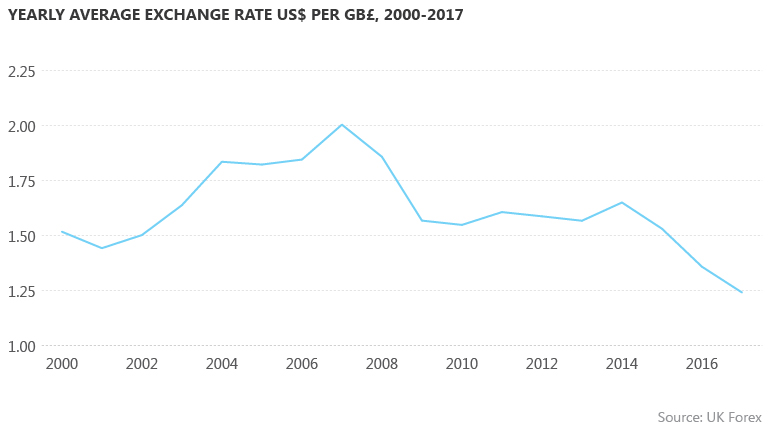

Exchange rate movements will define ultimate gas prices

As illustrated in Yearly average exchange rate US$ per GB£, 2000-2017, the pound-dollar exchange rate has seen a rapid decline since 2014 and continued to fall in early 2017. This is the result of a number of factors, including the slowdown in UK economic growth, uncertainty surrounding Brexit, and the postponement of UK interest rate hikes while rates are likely to rise in the US. Combined, these factors are likely to keep the pound-dollar exchange rate low until after Brexit. These developments will therefore put upward pressure on domestic gas prices in the UK. The exchange rate between the pound and the dollar will effectively have a significant say on the price UK customers will have to pay for their gas.

Demand will depend on carbon price and power fuel mix, not Brexit

Future UK gas demand will depend largely on the country’s future power generation mix, and that will be determined by the competitiveness of each fuel. The UK’s power industry will face exceptional challenges in the coming decades as it strives to meet medium- and long-term carbon emission reduction targets. The achievement of these targets will require a substantial expansion of the use of low-carbon electricity generation. The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) was developed to facilitate this change and has been complemented by the UK government’s addition of a ‘carbon tax’ on power generators and industry to increase the incentive to switch to lower-carbon sources of energy. In its 2014 budget, the government announced that the carbon price component of the floor price would be capped at a maximum of £18 per ton of carbon dioxide from 2016 to 2020 to limit the competitive disadvantage faced by business and reduce bills for consumers. This was extended to 2021 in the 2016 budget. Following the implementation of the UK’s carbon price floor, the European Commission considered – but ultimately rejected – a similar system to reform the ETS.

The EU has set targets for reducing emissions and increasing the use of renewables at a union-wide level, and the UK has been a leader in this and in developing environmental legislation. It appears unlikely the UK would renege upon these commitments in the post-Brexit period – such a move would be highly unpopular. Although membership of the ETS remains open to question (and its impact on UK carbon prices uncertain), it is worth noting the ETS has had little impact on the UK gas market. Instead, the carbon price floor set by the UK government will continue to be one of the main environmental policies affecting gas consumption. At the moment, gas is still seen as a bridge to a decarbonised economy.

The UK’s influence on Europe will slowly diminish

The UK is a member of a number of EU agencies, one of which is the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), which it will leave following Brexit. The UK has chaired the boards if ACER and the Council for European Energy Regulators for a number of years, offering ample opportunity to influence policy and regulatory developments. While most of the tasks of these agencies relate to cooperation among EU member states, some of their activities require, or may benefit from, collaboration with regulatory entities in third countries such as Norway and Russia. This is particularly relevant to infrastructure interconnections. This would therefore leave a window open for dialogue. Also, the UK has been ahead of most EU states in liberalising its energy markets, and the rest of Europe has been trying to emulate elements of the UK model. In the past, this has given the UK a higher profile and created many opportunities for the industry to share its knowledge, both directly and through consultancy services. Post-Brexit, it could be argued the dialogue will continue but the scale of the UK’s influence is likely to decline.

Brexit could hamper recruitment of services and labour from abroad

The UK’s oil and gas industry employs some 300,000 people directly and indirectly, and it is reliant to a great degree on people and professional services from abroad. As a result, the industry will face significant challenges if the Brexit negotiations result in restrictions on the employment of foreign nationals and higher taxes and tariffs on imported goods and services. These challenges may stimulate an increase in the provision of education and training schemes for local people and the establishment of new service companies in response to the industry’s needs. However, this will only happen with government support.

IPA Advisory provides advisory services along the full oil, gas and LNG value chain, from upstream development to downstream markets. Our experts provide techno-economic, commercial and market fundamentals analysis, as well as regional and global insight.

Colin Harrison, Managing Principal – Oil, Gas & LNG

Email: [email protected]

Zuzana Princova, Gas Market Specialist

Email: [email protected]

- Liked this article?

- Stay informed with exclusive, accurate and up-to-date energy news, analysis and intelligence. Sign up for 7-day trial access to more premium content. It's free!

- Get a free trial